To Sit or to Stand?

Students and Teachers Share Perspectives on the Pledge of Allegiance

October 1, 2021

To sit or to stand, that is the question.

House File 847 was enacted into law preceding the 2021-2022 school year. One major part of this new law requires all schools in Iowa to lead the Pledge of Allegiance daily in grades K-12. Representative Carter Nordman of Adel, Iowa, the leading proponent of this bill in the Iowa Legislature, stated that this bill was passed in hopes that it would bring Americans together, regardless of political affiliation.

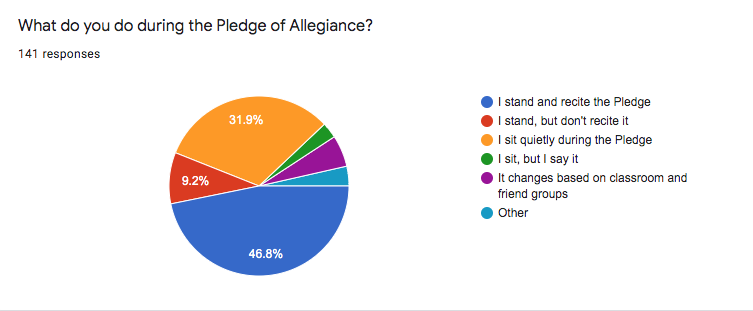

In September, the Mustang Moon sent out an email survey to the entire student body. One of the questions asked what students did during the pledge. Out of the 141 responses, reports show that 56 percent stood during the pledge and 34.7 percent chose to sit. Additionally, 5.7 percent said that their decision changed depending on classes and friend groups.

Students are not alone in being divided on reciting the pledge, as staff and administrators also see the nuances of this issue.

Superintendent Dr. Greg Batenhorst believes that freedom of speech and expression is “one of the cornerstones of our democracy.” He encourages students and staff to respect one another while exercising their rights.

While the stated intent of this legislation aims to create unity, he believes “It is going to take more than just a daily recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance to bring our nation together.”

Mount Vernon High School’s three social studies teachers have different perspectives on this issue.

Margo Massey states that standing for the pledge is a reflection of your respect and pride for your country, and to sit is to not be a proud American. “Initially when people weren’t standing up I actually was shocked,” she said.

She suggests that students may not be comfortable pledging to stand “under God” and stating that we are “indivisible.” “They don’t want to be robotic,” she said.

Massey observes that the entire student body stands for the national anthem at school events, but many sit for the pledge. She considers why this inconsistency is present, how reciting the pledge “is divisive because it forces you to choose.” She discusses how reciting the pledge requires more of a commitment than listening to the national anthem and showing respect silently.

Maggie Willems chooses to sit during the pledge, voicing her frustration that it’s mandated and not voluntary. She is skeptical of the claim that requiring the pledge will unify Americans. “This action is yet one of many in our cultural narrative of toxic nationalism,” she said. “Nationalism inherently views others as inferior — whether it excludes someone based on their ethnicity, another targeted group membership, this socially created perception of what it means to be a Great American is often exclusionary, and thus not patriotic.”

Willems went into more depth about the addition of the phrase “Under God.” This aspect of the pledge was added in 1948 to fight communism and has notably withstood the test of time. “This negates the idea of indivisibility,” she said. With the many religions, or lack thereof, that Americans practice today, it excludes a large portion of citizens.

Ed Timm views standing for the pledge as a way of showing respect and pride. However, he also notes that “If you’re doing it just because they are forcing you to do it then it’s an exercise of futility.” He appreciates our ability to choose and voices his respect for those who sit and for those who stand.

Although administrators remind students and staff to respect one another regardless of their decision, Timm said, “It’s natural that out of the corner of their eye people look at somebody and they roll their eyes one way or the other.” He believes that it may be hard, if not impossible, for people to control their involuntary judgments of people who disagree with them on this issue.

Mount Vernon’s Instructional Coach Tawnua Tenley served in the U.S. Army for four years after graduating high school. She views standing for the pledge simply as standing for what you believe in. “I think it is good to have the choice, it doesn’t make us more or less a citizen either way,” she said.

To sit or to stand? With opinions ranging from one end of the spectrum to the other, it is clear that our school is divided. Those who stand and those who sit appear to be trying to honor the same country in different ways.